|

THE SELVA MAYA

THE PEOPLE AND THE FOREST

|

|

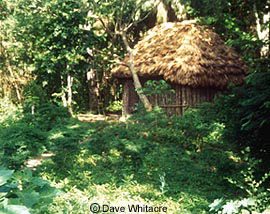

A typical house in a forest village

built

completely of materials from the forest.

|

Many people who live in the more remote villages of northern Pet�n participate in what has been called a "forest society" described in detail by anthropologist Norman

Schwartz (1990). While many new-comers to Pet�n rely mainly on slash-and-burn farming of corn and a few other crops, adherents to older petenero cultural ways rely much more heavily on the intact forest. While they may plant

corn at times, they are more likely to hunt in the forest for meat (or buy it from a neighbor who is a serious hunter), and to collect various forest products for sale.

|

|

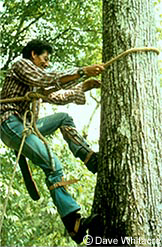

The chiclero climbs the tree

with the aid of climbing

spikes and a flip-rope.

|

Non-Timber Forest Product Industries

Chicle

Much as the Amazon Basin is noted for forest-extractive industries such as rubber-tapping and collecting of Brazil nuts, the Maya Forest is home to several important non-timber forest product industries. Most famous is the

collection of chicle, the latex of the chicozapote, chicle, or sapodilla tree (Manilkara zapota). At one time chicle was the primary elastic ingredient of chewing gum, and it is still used in this fashion, and

for other uses. The chiclero climbs the tree with the aid of climbing spikes and a flip-rope, and, using a machete, chops a herring-bone pattern of shallow cuts down to the cambium. A collecting bag is fastened at the tree's

base, to collect the flowing latex.

|

|

Nearly every good-sized

chicozapote tree in the

forest bears the scars

of repeated tapping.

|

Chicleros operate during the rainy season, usually organized into camps of a couple dozen men, often financed by contratistas, the camp organizers. This industry has thrived in the Selva Maya for more than a hundred

years, and dominated the economy from the 1890s until the 1970s, giving rise to a distinctive culture and regional pride evident among peteneros even today. This industry helps sustain a few thousand families in northern

Guatemala (and lesser numbers in Belize and M�xico), with an annual export crop usually worth a few million U.S. dollars.

|

|

Xate ("sha-tay") palm leaves in

a Guatemalan

airport,

awaiting

export to the U.S. or Europe.

|

Xate

Another important non-timber forest product industry is the xate (pronounced "shah-tay") palm leaf industry. This is an industry based on collection of palm leaves in the forest, for export to florists in the U.S.

and Europe. Leaves of at least three small understory palms of the genus Chaemadorea are harvested from beneath the intact forest, by men, boys, and less often women. The xatero walks many miles daily through the forest,

lopping (ideally) only one leaf from each plant encountered, collecting perhaps $10-12 worth of leaves in a day. The leaves are bought by intermediaries, sorted, and exported by air to florists abroad, netting on the order

of $3-4 million annually in foreign trade for Guatemala.

Allspice

|

|

This dog may earn his keep as a

tepescuintle (paca: Agouti paca) hunter.

|

Another local forest product industry is the collection of allspice, the traditional seasoning of pumpkin pie fame. Allspice comes from the fruits of a small understory tree,

Pimenta dioica, or pimienta gorda. The fruits are generally collected by lopping off the tree's smaller limbs.

All three of these non-timber forest product industries are valued highly by conservationists, because they depend on the existence of the intact forest. These industries represent ways in which many families can make a living,

or at least supplement their income, by using the forest in a non-destructive manner. Hence these activities represent viable economic alternatives to cutting down the forest and raising cattle or corn. Also worth noting

is that the monetary benefits of these activities--especially xate and pimienta collecting, which require minimal specialized skill, equipment, and investment--flow broadly into the hands of the rural poor, rather than being

concentrated in the hands of a few investors. Thus, these industries help support many families rather than just a few.

|

|

A typical rural kitchen in the Selva Maya.

|

Many conservationists believe that such forest-dependent industries, which give tangible economic value to the standing forest, are an ally in the fight to save these forests. In the absence of such perceived economic value,

the forests are more likely to be unsustainably logged or cut down and the land converted to farming and cattle ranching. In turn, the many people who partake in these ecologically sound forest-extractive industries comprise

a political constituency that can help ensure that government works to save these forests.

A less sanguine view of the utility of such non-timber forest products as an alternative to deforestation is provided by

Southgate (1998).

NEXT

9

|

|